Lionel Robbins didn’t understand science. Ravens do.

Lionel Robbins was wrong. Robin Hood was right.

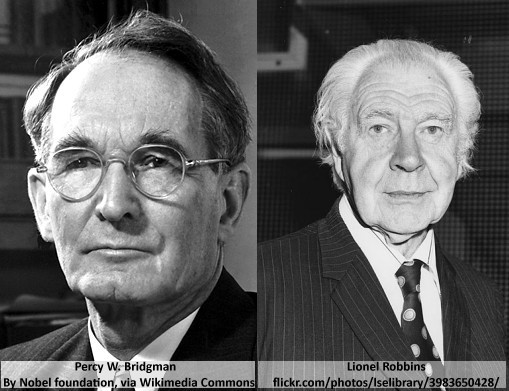

Bridgman and Robbins: They failed on scientific method

Bridgman and Robbins- Failed in scientific method

In 1927 the physicist, Percy Williams Bridgman put forward his view of science that had a huge influence on the social sciences in the 1930s and 1940s. This was called “operationalism”. For many decades now no philosopher of science has taken operationalism seriously. Bridgman’s main point was that we do not know the meaning of a scientific concept unless we have a method for measuring it.

Bridgman was wrong as simple examples show e.g. in 1909 Robert A. Millikan and Harvey Fletcher estimated the charge on an electron from the movement of oil drops in electric fields. They did not observe electrons but no scientists regarded the idea of an electron as an unscientific concept even though electrons are not directly observable

However, Bridgman’s operationalism has had a lasting effect. In “The Tragedy of Operationalism” Mark H. Bickhard comments

Operationalism has continued to seduce psychology more than half a century after it was repudiated by philosophers of science, including the very Logical Positivists who had first taken it seriously.

In economics, operationalism influenced Lionel Robbins, who in 1932 published “An essay on the nature and significance of economic science”. The influential claim Robbins made was that any use of “satisfaction”, or any internal state of mind, was unscientific: Satisfaction could not be directly measured. He gave this example:

If we tested the state of their blood-streams, that would be a test of blood, not satisfaction. Introspection does not enable A to discover what is going on in B’s mind, nor B to discover what is going on in A’s. There is no way of comparing the satisfactions of different people.

This is a straightforward example of Robbins following Bridgman’s misconception. It would be interesting to know whether, in later years, he learnt anything from his eminent colleagues in the Department of Philosophy, Logic and Scientific Method at the London School of Economics, Karl Popper and Imre Lakatos. As eminent philosophers of science, they could easily have corrected his mistake.

Popper and Lakatos -Eminent philosophers of science at LSE

The internal mental states of ravens

Although “satisfaction” and other mental states such as hate, love & etc are not quantified and measured directly, they can be part of theoretical discussions. A simple example: We may have reason to postulate that “Adrian dislikes Charles a bit, Bob dislikes Charles with a vengeance” so we predict that Adrian will sit next to Charles if the nearest empty seat is next to Charles but Bob will leave the room. This prediction, which uses an internal mental state,dislike, has an empirical test so it conforms to scientific method. (Also see Appendix – Satisfaction in use.)

Robbins (1932) would have wrongly categorised this theorising as unscientific because mental states cannot be directly measured (but, of course, neither can the charge on an electron). In the quote below if “stands above” means “greater than”, Robbins was quite wrong to say

To state that A’s preference stands above B’s … has no place in pure science.

Robbins may have refused to discern what is going on in other minds but ravens do not, as recent research has shown

Fears over surveillance seem to figure large in the bird world, too. Ravens hide their food more quickly if they think they are being watched, even when no other bird is in sight.

New Scientist says this “is the strongest evidence yet that ravens have a ‘theory of mind’ – that [ravens] can attribute mental states such as knowledge to others.”

Ravens have a theory of mind

“What is” , “what ought to be”

Robbins also emphasised the distinction between “what is” and “what ought to be”. “What is” concerns science. “What ought to be” does not. He believed that, as scientists, economists should concerned with “what is” and not with “what ought to be”. The Library of Economics and Liberty (2008) says

Robbins argued that the economist qua economist should be studying what is rather than what ought to be. Economists still widely share Robbins’s belief.

However, Robbins’ view that “what ought to be” ought not to be part of economics doesn’t justify his claim that terms like “satisfaction” can have no place in science – just because they cannot be directly measured. Along with Bridgman, he was wrong, simply wrong.

The Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility

The Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility (for utility read “satisfaction”) was used by earlier economists and political philosophers as a justification for taking from the rich to give to the poor.

The idea is that taking a bit from the rich reduces their level of satisfaction and giving it to the poor increases their satisfaction by a greater amount. So the overall level of satisfaction increases.

Robbins described The Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility (and for “utility” read “satisfaction”):

[1] The Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility implies that the more one has of anything the less one values additional units thereof.

[2] Therefore, it is said, the more real income one has, the less one values additional units of income.

[3] Therefore the marginal utility of a rich man’s income is less than the marginal utility of a poor man’s income.

[4] Therefore, if transfers are made, and these transfers do not appreciably affect production, total utility will be increased.

[5] Therefore, such transfers are “economically justified”.

For clauses [1], [2], [3] and [4], it is quite easy to construct theories with testable consequences. They are not inherently non scientific. In clause [5] “justified” clearly denotes a “what ought to be” statement.

Robbins further said

The Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility does not justify the inference that transferences from the rich to the poor will increase total satisfaction.

Assuming that by “justify the inference” Robbins means “predict”, he is wrong. Items [1] to [4]can be part of a scientific theory, empirically based, that does this. When he says

all that part of the theory of Public Finance which deals with “Social Utility” goes by the board.

Robbins was just wrong. His false argument has not demonstrated this at all.

This question remains: Is The Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility a moral (“what ought to be”) statement? The answer is not until clause [5]. Clauses [1-4] make no moral statement.

The Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility and taking from the rich

Many of us believe that, as a general rule, taking from the rich to give to the poor it increases the sum total of human happiness (clauses [1-4]) and some of us believe this is morally justified (clause [5]).

If Robbins had been correct and The Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility [1-4] were unscientific then the scientist within us might reject the whole thing. As Robbins was wrong we are free to use scientific methods to show that taking from the rich to give to the poor does usually increase the sum of human satisfaction – or as others call it “happiness”. We may then impose our own moral view.

After scientific analysis, we may also put on our moral hats and believe that redistribution is morally right. In short.

Bridgman was scientifically wrong

Robbins was scientifically wrong.

We are free to believe that Robin Hood was morally right.

Appendix – Satisfaction in use

Example 1 – Customer satisfaction

Supermarkets that keep shoppers happy (The ‘i’ April 12th 2016).

Waitrose has been named Britain’s leading supermarket for customer satisfaction for a second year, while Aldi has overtaken Marks & Spencer to become second-favourite.

Sainsbury’s and Morrisons came in fourth and ?fth place, respectively. Survey company Market Force — ‘ Information polled 6,648 shoppers.

The ‘i’ April 12th 2016

Example 2 – a bird watcher and friend

On the way to the pub

A dunnock – Very interesting to a bird watcher

Adrian and Bob are tired and thirsty from a days work and heading for their local pub. Across a congested road, they see a small brown bird in a hedge, which happens to be a Dunnock, a less usual variety of sparrow. From other observations we have the theory that Adrian is a bird watcher (e.g. he buys bird watching magazines) and using the theory that for birdwatchers the level of satisfaction of seeing this bird is higher than normal people we predict that Adrian is more likely than Bob to want a closer look. We can then further predict that Bob goes straight on to the pub and that Adrian struggles through filthy car fumes to get a closer look at the Dunnock.

This reasoning follows the accepted scientific methodology: Make a theory and test it. Our theory is that the satisfaction of seeing this bird in the bush is greater for birdwatcher Adrian than for normal Bob. It can be tested in a similar way to other theories. It fails if Bob crosses the road and Adrian goes onto the pub. Then the theory needs to be modified or discarded.

Example 3 – The Judgment of Solomon

Then the king answered and said …

Solomon had a hypothesis

That one harlot valued

The baby more.He just didn’t know

That inter-personal comparisons of utility

Were unscientific.In retrospect isn’t it amazing

That someone so ignorant

Could rule a kingdom.

Sex in Space, Belle Vue Press (1993)

1 Kings 3 v 16-28

Then came there two women, that were harlots, unto the king, and stood before him.

And the one woman said, O my lord, I and this woman dwell in one house; and I was delivered of a child with her in the house.

And it came to pass the third day after that I was delivered, that this woman was delivered also: and we were together; there was no stranger with us in the house, save we two in the house.

And this woman’s child died in the night; because she overlaid it.

And she arose at midnight, and took my son from beside me, while thine handmaid slept, and laid it in her bosom, and laid her dead child in my bosom.

And when I rose in the morning to give my child suck, behold, it was dead: but when I had considered it in the morning, behold, it was not my son, which I did bear.

And the other woman said, Nay; but the living is my son, and the dead is thy son. And this said, No; but the dead is thy son, and the living is my son. Thus they spake before the king.

Then said the king, The one saith, This is my son that liveth, and thy son is the dead: and the other saith, Nay; but thy son is the dead, and my son is the living.

And the king said, Bring me a sword. And they brought a sword before the king.

And the king said, Divide the living child in two, and give half to the one, and half to the other.

Then spake the woman whose the living child was unto the king, for her bowels yearned upon her son, and she said, O my lord, give her the living child, and in no wise slay it. But the other said, Let it be neither mine nor thine, but divide it.

Then the king answered and said, Give her the living child, and in no wise slay it: she is the mother thereof.

And all Israel heard of the judgment which the king had judged; and they feared the king: for they saw that the wisdom of God was in him, to do judgment.

King James Bible (1611)

Postscript 11th March 2018: Cardinal and ordinal

I have just come across A.C. Pigou’s Economic of Welfare, on EconomicsDiscussions.net (Article shared by Natasha Kwat). In the criticisms of Pigou’s ‘conditions of welfare’ Natasha includes:

(2) Pigou measures ‘welfare’ cardinally:

According to Pigou, welfare is measured in terms of utility or satisfaction. He regards social welfare as the summation of utilities of exchangeable goods and services to individuals. Economists do not agree with this view because quantitative measurement of utility is not possible. It is for this reason that modern economist’s measure utility ordinally.

May I give this example to Natasha and the any passing economist that might read this:

(2) Millikan measures ‘the charge on an electron’ cardinally:

According to Pigou, welfare is measured in terms of utility or satisfaction. He regards social welfare as the summation of utilities of exchangeable goods and services to individuals. Economists do not agree with this view because quantitative measurement of the charge on an electron is not possible. It is for this reason that modern economist’s measure utility ordinally.

Bridgman, Robbins and countless economists that have followed, have taken measurement to mean some sort of direct measurement. With this meaning, they and should have denied that Millikan measured the charge on an electron: Millikan measured the electric field that suspended small drops of oil. In the sense used by Bridgman and most economists since, he measured the strength of the electric field not the charge on the electron. Actually, not even that, he looked at some pointer on a device that “measured” the strength of the field.

What other argument could economists use for denying the place of cardinal utility in economic theories? Perhaps they would use Occam’s Razor. I have just found How Is Indifference Curve Analysis Superior to Marshallian Cardinal Utility Theory? by Sundaram Ponnusamy. He writes

According to the principle of Occam’s razor or the rule of parsimony, if two theories provide same result, the theory with the fewer assumptions should be preferred. Therefore, indifference curve analysis outweighs Marshall’s cardinal utility method in this regard.

My initial reaction that the usefulness of Occam’s razor is overdone. Especially as I am a fan of Paul Feyerabend’s Against Method: Outline of an Anarchist Theory of Knowledge:

[Feyerabend’s] critique is a reductio ad absurdum of methodological monism (the belief that only a single methodology can produce scientific progress)… He then demonstrates that [the features of methodological monism] imply that science could not progress, hence an absurdity for proponents of the scientific method.

However, let’s think of applying Occam’s razor to some statements using cardinal utility with Simon who is sitting next to me:

Me: Simon here are two statements:

A: I liked The White Countess five times more than The shape of water.

B: I liked The White Countess more than the The shape of water.

What is the difference in meaning?

Simon:

C: You liked them both and might see both films again.

D: You would pay a significantly higher price to see The White Countess.

If an economist applied Occam’s razor to statement (A). Simon could not have made the testable statement (D). With extra knowledge about my psychology and my finances he might even guess how much I would pay for a ticket.

Too many worries about scientific method.

Scientific method is … I’ve had enough now. If you have read this far so might you. Suffice it to say that science and scientific method isn’t and cannot be as clear as some pretend. In economics it’s less clear than in, say, physics. Although it is possible to get it wrong. Robbins did.

It is a fallacy that cardinal utility is inherently unscientific. It is way down the block chain of academic economics, part of the very small print that underlies much policy making. It still hinders the moral principle “Take from the rich to give to the poor“. Although this can conflict with other moral principles, it should not be dismissed as unscientific.

Why did Robbins do it?

I would like to know if Robbins had any motive to protect the rich and affluent and avoid the morality of redistribution. In The Libertarian Attack Against Liberty: Fake Patriots and False Gods, Joseph W. Burrell writes:

Lionel Robbins, a conservative professor at the London School of Economics, warned that governments must do absolutely nothing to feed the hungry, house the homeless, or provide jobs for the poor lest it create a really serious problem. He admitted that doing nothing would cause a lot of suffering and death but said that doing something would be in?nitely worse.

Is Burrell accurate? If he is, it suggests Robbins had political leanings to help him embrace Bridgman’s false reasoning.

See also: Feeding the geese and robbing the rich.

comment

TrackBack URL :

The way you speak of the Law of Diminishing Marginal Utility is false. It is a scientific law that applies only to Goods and Services. By saying it was justification to steal from the rich and give to the poor is absolutely false. Please edit that on your website or just don’t have a website at all if you aren’t going to be accurate.