GWP* should not be adopted by the IPCC

When GWP* is “net-zero”, CO2 & CH4 emissions are not zero.

To scientists of the IPCC’s AR6 Working Group 1,

GWP* should not be adopted by the IPCC.

This note is prompted by a concern for transparency in the IPCC process, and concern about GWP*, a new way to assess global warming potential (GWP).

The UK Government’s business department, The Department of Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy has the UK Government’s climate brief. From a Freedom of Information Request, I know that the Department has made a submission concerning GWP* to your working group. The Department has refused to tell me its contents.

GWP* is billed as “A new way to assess ‘global warming potential’ of short-lived pollutants”. It is one version of Global Warming Potential (GWP). GWPs are used to combine the greenhouse effects of different climate pollutants into one measure. There are valid criticisms of existing versions of any GWP, but in one aspect GWP* is worse than others, and particularly worse than the measure used in the Paris Agreement, GWP100. Switching from GWP100 to GWP* would weaken commitments that are given to reach ‘net-zero’ greenhouse gas emissions.

Background: The Paris Agreement

The Paris Agreement’s central aim is to strengthen the global response to the threat of climate change by keeping a global temperature rise this century well below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels and to pursue efforts to limit the temperature increase even further to 1.5 degrees Celsius.

UNFCC: What is the Paris Agreement?

There are two points about the Paris Agreement that I hope you recognise.

First, it is an agreement that aims to keep the rise in Earth’s average surface temperature during this century below a maximum value. (However, this value has not (yet) been exactly specified.)

The specification of a maximum temperature rise can give this result: High temperatures near the maximum for the rest of this century may be compliant with the agreement, if the maximum is not exceeded. In contrast, when temperatures are significantly lower than the maximum for most of the century, but the limit is exceeded in one year, the Paris Agreement is breached.

This is counter-intuitive because several decades of consequences, such as heat deaths, droughts, floods and storms can be worse than decades of less severe consequences, with one year of exceedance. The cumulative effects for the compliant scenario are likely to be worse than the non-compliant one. Using any reasonable version of degree day measure would support this.

Second, by global temperature, the Paris Agreement means Earth’s surface temperature, usually interpreted as Global Mean Surface Temperature, GMST. Limiting GMST is a proxy for limiting the threats of climate change, but, at any given time, surface temperature does not account for all these threats.

Another important cause of climate threats is the heat that has accumulated in the Earth by many past decades of the greenhouse effect. This warming can be referred to as ‘greenhouse warming’. (Greenhouse warming not the same as a rise in GMST, which is often incorectly referred to as Earth’s ‘warming’.)

A proportion of this greenhouse warming is heat in the atmosphere and surface of the Earth, which can be proxied by GMST. This part of greenhouse warming drives most of Earth’s weather, but it is a very small proportion of the total greenhouse warming : The rest of the accumulated heat collects below the Earth’s surface. Most of the accumulated warming (over 90%) is ocean heat content (OHC). To OHC can be added the latent heat of melted ice masses and thawed tundra. This non-surface heat causes sea rise, rapid intensification of storms and positive climate feedbacks, carbon cycle and otherwise.

The intensification of storms is making them more dangerous, particularly as they penetrate land masses further, with greater payloads of moisture.

Increased OHC is destroying life in the oceans.

Short lived climate pollutants (SLCPs) and long-lived climate pollutants (LLCPs).

Greenhouse agents or ‘climate pollutants’ are often divided into two categories: short lived climate pollutants (SLCPs) and long-lived climate pollutants (LLCPs). Methane, CH4, is the most important SLCP: It degrades in the atmosphere with a half-life of about a decade. Its greenhouse heating has little effect on GMST after a few decades.

The most important LLCP is carbon dioxide, CO2, which lasts very much longer. It is slowly absorbed into sinks, which can re-emit the CO2 if atmospheric concentrations fall. Nitrous oxide, N2O, is a secondary LLCP. LLCPs effects on GMST lasts for centuries – unless LLCPs are extracted from the atmosphere by positive action, such as Carbon Dioxide Removal.

Although methane and other SLCPs stay in the atmosphere for a comparatively short time, the greenhouse warming that they trap stays in the Earth for centuries, nearly all below the surface. As noted earlier, this sub-surface heat raises sea levels, causes rapid intensification of storms, melts ice sheets and thaws permafrost. It is triggering carbon cycle feedbacks and other climate feedbacks.

Many of the scenarios in IPCC reports include Carbon Dioxide Removal (CDR) from the atmosphere. This means some emissions of CO2 have a short residence in the atmosphere, making them emissions of SLCPs. The temporary residence of this CO2 still stores greenhouse heat in the Earth that lasts for centuries. CDR does not simply reverse the effects of CO2 emissions.

The Paris Agreement does not consider the totality of greenhouse warming (or continuous warm temperatures near the Paris maximum): It only sets a limit for surface temperature, GMST. Concentration on surface temperature and ignoring accumulated heat downplays the importance of SLCPs and overestimates the benefits of CDR.

Global Warming Potential

The Global Warming Potential (GWP) is a measure of how much energy the emissions of 1 ton of a gas will absorb over a given period of time, relative to the emissions of 1 ton of carbon dioxide (CO2). The larger the GWP, the more that a given gas warms the Earth compared to CO2 over that time period. The time period usually used for GWPs is 100 years. GWPs provide a common unit of measure, which allows analysts to add up emissions estimates of different gases (e.g., to compile a national GHG inventory), and allows policymakers to compare emissions reduction opportunities across sectors and gases.

Understanding Global Warming Potentials, US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA)

GWP100 is a measure of the heating that is caused over 100 years by a particular climate pollutant relative to a similar amount of CO2. GWP100 equals 1 for CO2 (by definition). N2O has GWP100 of 298 because over 100 years 1 tonne of N2O causes 298 times more greenhouse warming than 1 tonne of CO2. When a mixture of gases is emitted, GWP100 is calculated separately for each component. These are added together to form the GWP100 measure for the mixture.

Other timescales for measuring the greenhouse warming have been considered. When the IPCC introduced the idea of GWPs in 1990, it considered three different timescales for GWP: 20 years, 100 years and 500 years. The corresponding GWPs are denoted as GWP20, GWP100, GWP500. The 1990 IPCC report says:

These three different time horizons are presented as candidates for discussion and should not be considered as having any special significance.

Later the IPCC chose GWP100, as the measure. Now the focus is on avoiding dangerous climate change in the next thirty to forty years, the choice of GWP100 should be reexamined: A shorter timescale is appropriate.

A shorter timescale would emphasise the climate damage of emissions of SLCPs, methane in particular. Currently accepted values for methane are 34 for GWP100 and 86 for GWP20. Measuring GWP over 20 years increases its weighting in calculations based on GWP100 by 2.5 times.

This is not just academic, these measures affect climate policy as noted in the EPA quote above. However, if GWP100 is inappropriate, GWP* seems worse.

GWP*

Like any GWP, GWP* combines the effects of the emissions of a mixture of greenhouse gases and relates these to equivalent emissions of CO2 that would cause similar effects.

GWP* has two components, one for LLCPs (eg. CO2, N2O) and one for SLCPs (e.g. methane).

The first component is the same as other measures like GWP100. GWP100 is a measure of the heating that is caused over 100 years by a particular climate pollutant relative to a similar amount of CO2. GWP100 equals 1 for CO2 (by definition). N2O has GWP100 of 298 because over 100 years 1 tonne of N2O causes 298 times more greenhouse warming than 1 tonne of CO2.

The second component of GWP* tries to take account of the fact that SLCPs reside in the atmosphere for a limited time and their effect on GMST is short lived. Cutting methane emissions now will have little effect on GMST in 50 years’ time.

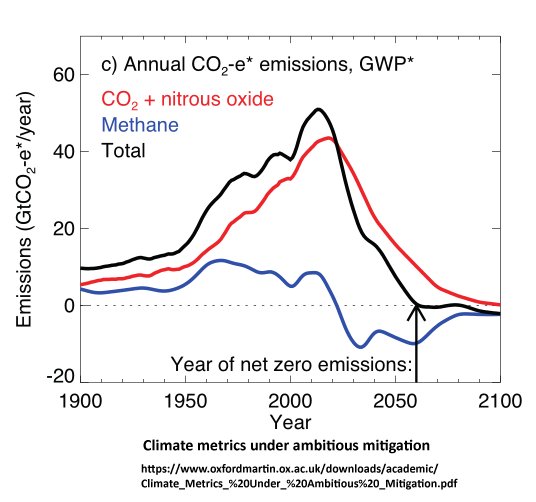

GWP* has been designed to try to take account of this difference. It does so by relating the second component of GWP* to the rate at which emissions of SLCPs are changing: If SLCP emissions are falling GWP* is reduced. If SLCP emissions are rising GWP* is increased. This is explained in A solution to the misrepresentations of CO2-equivalent emissions of short-lived climate pollutants under ambitious mitigation.

In the following CO2 should be taken to represent all LLCPs and CH4 taken to represent all SLCPs.

Net-zero GWP* is counter-intuitive.

Its definition makes it possible for GWP* to become zero or even negative, when neither emissions of CO2 nor methane are zero – if emissions of methane are falling fast enough. If GWP* replaces GWP100, it will be possible for countries to claim a net-zero GWP while still emitting significant amounts of greenhouse gases.

With a policy which asks for “net-zero emissions by 2060”, GWP* allows keeping CH4 emissions at their current level – or even higher – until 2040, when a decline in methane emissions can bring about the “benefit” of “net-zero GWP* emissions” because methane emissions will then be falling. (As noted above, “net-zero GWP*” does not require CO2 emissions or methane emissions to be zero.)

Oddly, added CH4 emission in the short term can bring forward the date for net-zero GWP* by setting the atmosphere in a state, which enables a greater rate of fall of CH4 emissions later in the century. This is counter-intuitive – It is clearly counter-intuitive.

More generally, setting targets which aim for “net-zero GWP*” emissions of GWP* by a specific date, decades in the future, benefits a policy of delaying cuts even of CO2 emissions, when compared to other versions of GWP.

Adoption of GWP* would dismiss a sensible strategy

Use of GWP* would dismiss the strategy proposed by Xu and Ramanathan in Well below 2 °C: Mitigation strategies for avoiding dangerous to catastrophic climate changes. A crude representation of this might be:

- Cut CH4 emissions now

- Cut CO2 emissions as soon as possible

- Extract CO2 from the atmosphere.

These proposals would score badly, when measured against a policy, which aims to have net-zero GWP* emissions by, say, 2060, because they cut methane emissions too soon. This is also counter-intuitive.

The other problems with GWP* are also problems in the Paris Agreement as discussed above. Its concentration on a peak value of Earth’s surface temperature ignores the effects of the heat accumulating below the immediate surface of the Earth. GWP* also encourages policies, which set aside the effects of decades of high temperatures in order to prevent a short term breach of the Paris maximum.

GWP* should not be adopted by the IPCC.

Appendix: Email to scientists of the IPCC’s AR6 Working Group 1.

GWP* should not be adopted by the IPCC

Although I am not a climate scientist, climate change has concerned me for well over 30 years. I have followed significant developments in climate science and climate policy. In the 1990s I ran conferences in York, England about climate change and the economy.

However, I am not conversant with the protocols of the IPCC, so I hope you will forgive this unorthodox means of contacting you, a scientist involved in IPCC AR6 WG1.

The reason for this contact is that I have strong doubts about the proposal for assessing the ‘global warming potential’ of short-lived pollutants. I think the UK Government’s business department may be promoting, this new measure, GWP*.

I have come to this conclusion from picking up various hints, and think it significant that my freedom of information request concerning communications between the Department and WG1 has been refused.

Of course, my reading of the science and policy context may be incorrect. Please let me know, if you have reasons to think I am wrong.

My worries also concern the Paris Agreement. Briefly, the worries are:

- The Paris Agreement specifies a maximum

temperature, side-lining the effect of long periods of raised temperatures, which are below the maximum.

- The Paris Agreement ignores the accumulated ‘greenhouse’ heat in the Earth, which is having significant consequences, like sea level rise, the rapid intensification of storms, feedbacks from thawing tundra and the extinction of many species in the oceans.

- When emissions of climate pollutants

(mostly greenhouse gases) are measured by GWP*, GWP* can be zero (or ‘net-zero),when neither CO2 emissions nor methane emissions are zero. This means that a commitment to reach net-zero GWP* by a certain date emits more pollutants than a net-zero commitment

for any other measure of GWP.

- Using a target of reaching net-zero GWP* by a year a few decades in the future, encourages a policy of delaying cuts to methane emissions, and, if I have understood correctly, even increasing them in the short-term. This is contrary to the strategy proposed by Xu and Ramanathan in Well below 2 °C: Mitigation strategies for avoiding dangerous to catastrophic climate changes.

I append my note: “GWP* should not be adopted by the IPCC“.

I have not found all relevant emails. Feel free to point colleagues to the web version of this note at GWP* should not be adopted by the IPCC.

Postscript: GWP* and the Climate Change Committee.

12 December 2020

Agricultural emissions discussed by the authors of GWP*

In Agriculture’s impact on climate: the science, not the headlines, Michelle Cain et al. argue that gently falling methane emissions cause no further warming. By “warming” the authors are referring to the target of a maximum surface temperature in the Paris Agreement. They say:

- If limiting global warming is the goal, mitigation options should be evaluated in terms of reductions in temperature

- this would make the evaluation measure consistent with the Paris Agreement temperature target

Here “limiting global warming” clearly means giving a maximum limit for the rise in Earth’s surface temperature. This is sidelining the totality of greenhouse warming (which includes Ocean Heat Content). It also encourages policies, which allow decades near the maximum surface temperature in order to avoid a year or two, which exceed the maximum.

The authors suggest that “a (slightly) more realistic scenario for UK agriculture” is for “UK agriculture’s contribution to global warming [be] reversed back to 1990 levels by mid-century”. It would be surprising if the coal industry were given a similar target.

The Climate Change Committee reject GWP*

A report by the Committee on Climate Change, Land use: Policies for a Net Zero UK, rejects changing from GWP100 to GWP* because that would delay reductions in methane emissions:

Keeping warming to the 1.5°C end of the Paris Agreement long-term temperature goal will require rapid reductions in global emissions of long-lived GHGs to reach net-zero. Reductions in global methane emissions, including from the agricultural sector, will also be critical.

• Global methane emissions are likely to need to fall to help offset the loss of climate cooling from aerosol pollution.

Reducing biogenic methane emissions from UK agriculture will have unambiguous benefits for the global climate. Given the economy-wide net-zero GHG emissions target, official accounting in the agricultural sector should continue to use the GWP 100 metric required for consistency with national and international frameworks.

In Reducing UK emissions, 2019 Progress Report to Parliament, the Climate Change Committee did address the issue of Ocean Heat Content, the major part of greenhouse warming:

Ocean heat content increased to record levels in 2018. More than 90% of the additional energy trapped in the climate system by raised greenhouse gas concentrations ends up in the oceans, making ocean heat content a more consistent indicator of human influence on the climate than global mean surface temperature

The Committee has not mentioned Ocean Heat Content since. Increased OHC would be another reason to reject the use of GWP*.

See also: Paris Agreement dodges cumulative effects.

comment

TrackBack URL :

Hello Geoff, in spite of your blog and appeal to the IPCC you seem to have entirely misunderstood how GWP* works. You are making the fatal error of treating fossil fuel leakage of effectively new methane (non-cyclical) with cyclical methane from ruminants. You are not the only one to misunderstand, the science really isn’t as difficult to understand as you seem to be making it out to be.

Your example of oil and gas companies planning to reduce fossil fuel leakage and then claiming to be “net zero” is bogus, because they are STILL emitting ALL NEW carbon into the atmosphere, which is ADDING to warming. You could argue that it is cyclical if you like but only if your cycle is measured in hundreds of millions of years, which I’m not sure is a convincing argument. Contrast that with methane from ruminants where the carbon is cycling round through the cow, the atmosphere, the grass and the soil, repeat ad infinitum. As long as the ruminant population is static then there is no new carbon being emitted. Fortunately GWP* ‘takes account for both situations but judges only one of them harshly even though both are judged correctly.

Finally, you seem to be of the belief that the CCC are correct in their assessment of the usefulness of GWP*. I can confirm that the Land Use report you yourself have highlighted, is as full of holes as a Swiss cheese. I find this alarming as this body is supposed to be recommending policy to the govt and to Parliament. If you like I can supply my copy to you with all of the problem areas highlighted in red. I’ll warn you, there are quite a few. What I find particluarly galling about it is that they are basically and shockingly saying that GWP* is extremely inconvenient to them as it raises many issues with their previous report to Parliament. What shines through above all else is their willingness to continue down their chosen path of throwing agriculture under the bus and they’re not for turning as they’ve invested so much in that policy recommendation

Please feel free to e-mail me back Geoff and we can discuss further.

Kind regards

Tom Johnston