A little help from Land Value Tax

Land value tax could help bring a little fairness

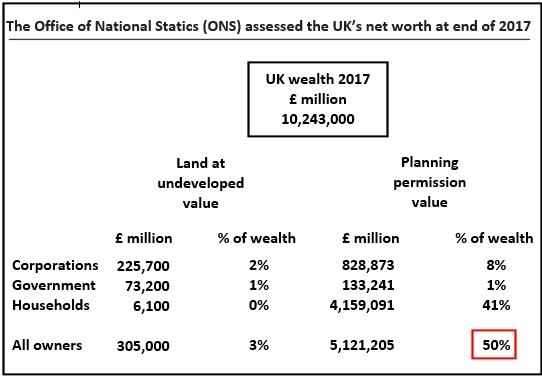

Planning permission is 50% of UK wealth

The right to have a building on a plot of land makes land valuable. Without this permission the value of land falls to a small fraction of this value. Using data, mostly from the Office of National Statistics, I have calculated that half the wealth of the UK can be traced to these rights, which can also be called planning permission.

The planning system enriches landowners.

Granting planning permission to build a house increases the value of land. A plot of agricultural land big enough for a house increases its value enormously. In York a plot of land worth £500 increases to roughly £200,000, several times more on the outskirts of London. The increase is called planning gain. Planning gain generates for wealth for landowners, which, in turn adds to the price of a new house.

I have estimated that the total planning gain in the York Local Plan is of the order of £2 billion. This enriches a handful of landowners, but it enriches others too.

House price inflation gives to the baby boomers, takes from the young

In The Baby Boomers housing bonanza, I reported how the rich and affluent got a substantial increase in their wealth through the housing market, while the poor paid more rent. Using house price data from the Land Registry, I found :

Adjusting for inflation between 2000 and 2010, I found that property of the most affluent areas increased by just over eight times the average income in 2010. Property prices in the least affluent are rose by a factor of two. However, according to the 2011 census, only 20% of households in the least affluent areas own their homes. In the most affluent areas this rises to 90%.

Summary: House price inflation has given most households in the most affluent areas large increases in their net wealth, at the same time most households in the least affluent areas will have paid increased rents as noted by the Institute of Fiscal Studies:

Relative to the general price level, the average (median) private rent paid in the mid 2010s was 53% higher than that in the mid 1990s in London and 29% higher in the rest of Britain.

Don’t crash the banks

How can the unfairness of the housing market be tackled? The bonanza handed to landowners and house owners may be hard to recover.

It is possible for government to create the conditions so that starter homes could be provided at a fraction of current prices. This would mean managing the planning system so that the value of planning permission was drastically reduced. One problem is that planning permission is half of the UK’s wealth. As, Andy Haldane, Chief Economist at the Bank of England, has said:

If additional housing supply was to cause sharp declines in house prices, this might raise concerns about the adequacy of mortgage lenders’ capital positions and hence raise financial stability concerns.

That means very cheap mass housing could crash the banks. Apart from arguments of fairness, it is hard to see a policy which destroyed half of the country’s wealth (and crashed the banks) being politically possible. Cooling the housing market might get support (especially from the less wealthy) but there are limits to a policy which provided mass housing that was very cheap.

An additional option: land value tax

It may be desirable to have a managed supply of very cheap housing, but the political power of house owners would limit such policies. However, there are other options. Land Value Tax (LVT) is one with a long history. It is supported by a range of political opinions, from the New Economics Foundation to the Adam Smith Institute . NEF describes the funding in local authorities in How a land value tax can pull local authorities out of a crisis:

Hundreds, if not thousands, of parks, playgrounds, libraries and children’s centres have been sold off or closed down. Subsidies for local buses have been reduced by almost half. Vital public health services, such as support for alcohol and tobacco addiction, have been cut back to a level described as “inadequate” by the British Medical Association. Homelessness prevention and support services have been cut by almost half, and …

They go on to point out:

Moving to a system of land value taxation could improve the fairness and efficiency of local business taxes, while also helping to reverse a portion of the funding cuts to local authorities. Unlike commercial property itself, the value of the land beneath it is largely beyond the control of its owner. The value comes mainly from the amenities and infrastructure in its immediate proximity, and the collective efforts of the communities that live and work in the surrounding areas.

At a different end of the political spectrum, support for a land value Tax comes from the Adam Smith Institute. In Land value tax versus urban sprawl, Amos Wollen wrote:

In this regard, paying LVT is not dissimilar to paying for a parking ticket. If John purchases a plot of land over which he demands autonomy and of which he demands the state’s protection, then he pays a rent back to the community. After all, if I ensnare a flat chunk of the universe with a picket fence and call it my own, I have taken land from the commons. Land that naturally belongs to everyone. Unearned capital that was given to us by nature. Therefore, it seems plausible that I owe a small debt of reimbursement to the community.

It’s not often the New Economics Foundation and the Adam Smith Institute agree.

Land Value Tax does not, by itself reverse the injustice to the poor and the young. However, it does tax the gains granted to property owners by planning permission, which is a step in the right direction.

Postscript 1: Will this government act?

An article in The Times, in February 2020, Rishi Sunak budget: Tories ‘to save high street’ with land tax to replace business rate reported:

In his first budget Rishi Sunak, the chancellor, will announce a “fundamental” review of the business rates system amid concerns that it is penalising high street retailers.

The current system of business rates is based on shop rental values and is calculated every five years. The levy is paid by tenants, rather than landowners.

It is viewed as outdated because companies that need a presence in town centres pay higher rates than online and out-of-town rivals.

The review will examine proposals for a tax on the land rather than buildings based on its “permitted planning” use.

Postscript 2: Failed comment on an article in Inside Housing

I signed up to Inside Housing to make the following comment on We need more affordable homes to support the recovery, so why are we introducing measures that will deliver fewer? By Olivia Harris, Chief Executive of Dolphin Living:

“The average house price in London is just under £500,000”

For new housing nearly all of that £500,000 is accounted for by planning gain, which enriches the land owner. London itself may be dense at 52 ppl/ha but the rest of the regions (including the “crowded south east”) have densities less than a tenth of London – and London is not dense compared to other cities like Paris..

We are not short of land but the new housing is constrained by the planning system, cheating the poor and the young. If this racket were sorted and modern prefabrication methods were used, starter homes could be nearer £20,000.

Why not?

#94: Starter homes for £20K

https://www.brusselsblog.co.uk/tips-on-climate-planning-and-the-economy/#94

comment

TrackBack URL :

It makes no economic sense to want to reduce land values. Firstly they offer the possibilty of deadweight free tax revenues. The cost of taxing benefical activities should not be underestimiated,

Secondly, aggregated land values are a measure of resource allocation. Reducing them means increasing costs and/or reducing welfare.

Like the high aggregated value of labour and capital, high land values only cause inequality/affordabilty issues if their returns are not justly distributed.

It is the moral conflation of land and capital that causes inequality, thus affordability issues. Its is somewhat perverse to blame planning/supply for this.

Land only gains a selling price due to the unequal distribution of the returns to land, thus is a measure of economic injustice.

The effect of a 100% tax on land’s rental value is to drop it’s selling price to zero. It does so by income transfer, typically to those that find housing unaffordable now.

That combination of average HP’s dropping by 65%, while the disposable incomes of typical households increasing >£10K pa, results in housing becoming as affordable as it could possibilty get for the groups in society suffering from affordabilty issues now.

Furthermore, such a tax allows the market to rationalise our existing housing stock ,which is grossly misallocated at present. This cuts costs, instead of adding to them by building the numbers/type currently projected.

The supply-side analysis of housing issues is no doubt driven by an ideological distaste for government interference in the market. But free markets are not fair thus optimally effecient ones. Which is why we need laws, rules and indeed planning regulations.

What is missing is an honest discussion about the ethics of excluding others from a valuable natural resource without paying them compensation. If that were to occur, the root causes of many issues, like housing becomes clear.

Its a fact that economists, politicans and commentators seem to extremely reluctant to have this discussion.