Climate change and town planning

The second of two blogs commenting on recent reports from the Committee on Climate Change.

This encourages the Committee to consider an extended version of town planning.

Climate change and town planning

Professor Sir Ian Boyd has just retired from his position as chief scientist at Defra. In Climate change: Big lifestyle changes ‘needed to cut emissions’, the BBC’s Roger Harrabin reported him as saying:

People must use less transport, eat less red meat and buy fewer clothes if the UK is to virtually halt greenhouse gas emissions by 2050

Sir Ian warned that persuasive political leadership was needed to carry the public through the challenge. One aspect of such leadership would be to inform the public about the severity climate change and the big lifestyle changes ‘needed to cut emissions’. [Note: Public campaigns]

In Building a Zero Carbon Economy – Call for Evidence, the Committee on Climate Change noted:

Previous CCC analysis has identified aviation, agriculture and industry as sectors where it will be particularly hard to reduce emissions to close to zero, potentially alongside some hard-to-treat buildings.

Aviation is a hard-to-reduce sector but may be treated by financial disincentives and FlagSham (Flight Shaming). Similarly, some progress on agricultural emissions may be made by taxation of animal products together with public shaming. To a large extent industry will follow the incentives that government set – but may lobby to prevent them.

In addition to public campaigns, some lifestyle changes suggest obvious policy options such as removing subsidies and increasing taxation (e.g. in the case of fossil fuels and animal husbandry [Note: Subsidies for fossil fuels and animal husbandry]).

‘Big lifestyle changes’ must include substantially reducing personal vehicle ownership as the House of Commons Science and Technology Committee has noted:

In the long-term, widespread personal vehicle ownership does not appear to be compatible with significant decarbonisation.

For a section of the population this could bring considerable benefits: Life with less car traffic would obviously be pleasanter. It could also be much cheaper. When he was European Environment Commissioner, Carlo Ripa di Meana commissioned a study which showed the enormous expense of allowing cars in towns. A press release from the European Commission in 1992 said:

Is it possible, and if so to what extent, to conceive of a city which will operate more efficiently than the type of cities we have at present, using alternative means of transport to the private car?

The answer provided by the study is positive, even in purely financial terms: the car-free city costs between two and five times less (the costs varying depending on the population density of the city).

Carlo Ripa di Meana was sacked soon after. The full report was never translated from the original French and consigned to the archives of the European Commission. An English translation would be welcome so that the conclusions could be examined and understood.

The lead given by the Office of Science and Technology suggests eliminating ‘widespread personal vehicle ownership’ to achieve ‘significant decarbonisation’ but there are other aspects of living that must change to achieve lifestyles with low greenhouse gas emissions: diet, food production, employment, building methods & etc. At present, most of these are outside the domain of town planners but to contribute to changing our dangerous trajectory on climate and related issues town planning must incorporate these [Note: related issues].

Without completely throwing away the insights that economists have about the operation of markets in our economy, it is time for a design-led approach to find low-carbon lifestyles that work on a local level. This would become an enhanced form of town planning, Enhanced Town Planning, which needs inputs from “engineers, economists, climate scientists, agronomists, house builders, architects, transport planners, town planners & all of us”.

Elsewhere, I have suggested two new institutions that could help:

The Committee on Climate Change has had a response from the Royal Town Planning Institute [Note: RTPI evidence]. However, the RTPI has not yet engaged with the scale of the climate problem. For example, their publications have no mention of “remaining carbon budget”. In particular, Planning for Climate Change – A Guide for Local Authorities has little means of curbing car ownership except minor encouragement. They say:

- Increase the proportion of trips in the local area made by sustainable modes, particularly active travel modes, by:

- giving comparative advantages to sustainable travel – for example by placing cycle parking closer to a main entrance than car parking (other than disabled parking);

- implementing travel plans (unless the scale of the development is small) so as to reduce greenhouse gas emissions;

- providing for safe and attractive walking and cycling opportunities, including secure cycle parking and, where appropriate, showers and changing facilities;

- managing the provision of car parking (including consideration of charging for use), so that it is consistent with cutting greenhouse gas emissions, including the provision of electric vehicle charging infrastructure; and

- improving public transport and utilising a travel planning approach.

This is limp stuff, moving a few parking spaces on the Titanic. The RTPI should know that persuading motorists to use cars less had little effect as research by the University of Leeds found. This was also the experience in the “sustainable” development at Derwenthorpe, York. [Note: Choice based car use].

The use of a private car can exhaust the whole of a personal remaining carbon budget [Note: Remaining carbon budgets and cars], so reducing the scale of personal vehicle ownership is the top priority.

If fewer cars, less flying less and eating less meat, were to lead to lower levels of overall consumption GDP would fall. That is degrowth. There are several ways to have degrowth and full employment. An old one of mine, improved by Prof Kim Swales was a commissioned report to the European Commission: A macroprudential proposal for employment. This proposal supports the bottom of the labour market would keep full employment as GDP falls. In economist’s terms that less productive jobs. In other terms it’s making jobs less stressful & more pleasant. (There are, of course, other proposals that would have a similar effect.)

Enhanced town planning: an example for the world

The population of the UK is 0.9% of the World’s population. The UK’s greenhouse gas emissions are 1.8% of global greenhouse gas emissions, much larger than the global average [Note: consumption emissions] but overall the UK is a small part of the problem. Apart from reducing our small percentage (but excessive) of global emissions, what can be done in the UK?

Is the answer ‘we can lead the world’? The RTPI claim the UK has a leadership position in environmental planning and BEIS make claims of leadership. Both these claims are hollow [Note: UK leadership claims]. However, the UK has a rich history of town planning, like the model villages of Victorian philanthropists: New Lanark, New Earswick, Saltaire, Port Sunlight and Bourneville. These were followed by the garden cities of Letchworth and Welwyn, conceived by Ebenezer Howard, which were separate cities with densities high enough to support urban life but small enough to allow easy access to the countryside. These settlements were planned before the private motor car became mass transport.

More recent examples of planned towns are Milton Keynes and Cumbernauld: Towns built to accommodate cars and attempt to resolve the conflict between cars and people. It is academic to ask whether Milton Keynes and Cumbernauld succeeded, if the proposition that ‘widespread personal vehicle ownership’ is not compatible with sustainable living is recognised. We should not build new settlements to accommodate cars but find ways of planning them out of our lives.

Town planning and the Committee on Climate Change

Although the Committee on Climate Change has published work on many aspects of climate change, there seems little that recognises the importance of town planning in bringing about lifestyle changes to curb greenhouse gas emissions quickly enough to save the climate.

NOTES

[Note: Public campaigns]

The Committee on Climate Change should advise the government to run campaigns to advise the UK Government to use public campaigns lead public thinking on climate change, pointing out the changes that need to be made to lifestyles.

There have been successful campaigns on smoking, seatbelts and drink driving, when supported by changes in the law. The campaigns may have influenced the public to support or acquiesce to these changes.

In 2009, Colin Challen MP suggested that the Government’s Act on CO2 campaign should be given more prominence:

He is already collecting signatures for a petition demanding a televised debate on climate change in the General Election campaign and said two hours of coverage each week should be dedicated to explaining the “gravity” of the situation.

Mr Challen said: “The Government’s Act on CO2 campaign has been moderately successful, but it needs a lot more attention given to it. This problem is not going away.

“We have to recognise the importance and critical nature of climate change to the UK. If that requires a change in the BBC Trust’s deeds, or possibly doing something through Ofcom, there’s no barrier to this.”

[Note: Subsidies for fossil fuels and animal husbandry]

Vox reported:https://www.vox.com/2019/5/17/18624740/fossil-fuel-subsidies-climate-imf

The International Monetary Fund periodically assesses global subsidies for fossil fuels as part of its work on climate, and it found in a recent working paper that the fossil fuel industry got a whopping $5.2 trillion in subsidies in 2017. This amounts to 6.4 percent of the global gross domestic product.

Feeding the problem from Greenpeace reported:

Taking into account CAP payments based on farm size, as well as payments that support production of livestock directly, between € 28.5 billion and € 32.6 billion go to livestock farms or farms producing fodder for livestock – between 18% and 20% of the EU’s total annual budget.

[Note: Related issues]

In the UK, house prices have risen so that home ownership is not available to large section of the population. Much of the cost of these is planning gain, which is paid to landowners. The rise in house prices is transferring wealth from the young and the poor to the old and affluent.

High housing costs also have the effect of raising the cost of living for the least affluent and low paid. This means they must earn more by being more productive and increasing their contribution too GDP and, via the Kaya identity, increasing carbon emissions.

[Note: RTPI evidence]

The Royal Town Planning Institute responded to the CCC’s Zero carbon economy: Call for Evidence.

The UK government should also seek to share and export the UK’s planning expertise, particularly concerning environmental planning, in which it is a world leader, to other markets and nations.

They made these points:

- – Aviation policy should help modal shift from short-haul air travel to high speed rail

- – Distributed and renewable energy generation, heat networks to be encouraged

- – Also electric vehicles, smart meters and digital mobility platforms

- – Planning authorities should increase housing supply, ensuring inclusive street design

- – Planning can facilitate more sustainable modes of transport and reduced travel demand

Note 6 references Harris, Settlement patterns, urban form & sustainability which says:

Settlement patterns and urban forms that promote sustainable mobility play a critical role in reducing transport emissions, with larger settlements, higher densities and mixed land uses reducing the need to travel by car.

The RTPI also say:

Working across government departments remains poor, and this undermines the government’s ability to bring together housing (MHCLG), infrastructure (BEIS, DfT, DCMS), and environmental measures (Defra) in a concerted way that produces sustainable development.

[Note: Choice based car use]

The research by the University of Leeds, Carbon reduction and travel behaviour: discourses, disputes and contradictions in governance found:

We have suggested that in this English and Scottish case study decision-makers accept the argument that choice-based approaches will lack effectiveness in reducing carbon, and that substantial change requires changing the conditions and circumstance which shape possible behaviours. The question is whether the low expectations for choice-based approaches give support to a recommendation that policy attention should shift from ‘choice-based approaches’ to measures designed to influence the contexts in which people make decisions?

The publication for the Joseph Rowntree Foundation, Making a sustainable community: life in Derwenthorpe, York, 2012–2018, also shows the limitations of choice-based approaches :

Parking is a key issue for many people, with 1.1 allocated car spaces per property; this causes conflict between neighbours, despite initiatives such as a new bus route, bike vouchers and a car club scheme designed to encourage only one car per household. It was clear that more far-reaching policies are needed for a one-car-per-household policy to work, including earlier and better public transport, consideration of incorporating this policy into title deeds/rental agreements, and/or clearer options for visitor/overflow parking at the perimeter or off-site.

[Remaining carbon budgets and cars]

There are several way of interpreting estimate of remaining carbon budgets.

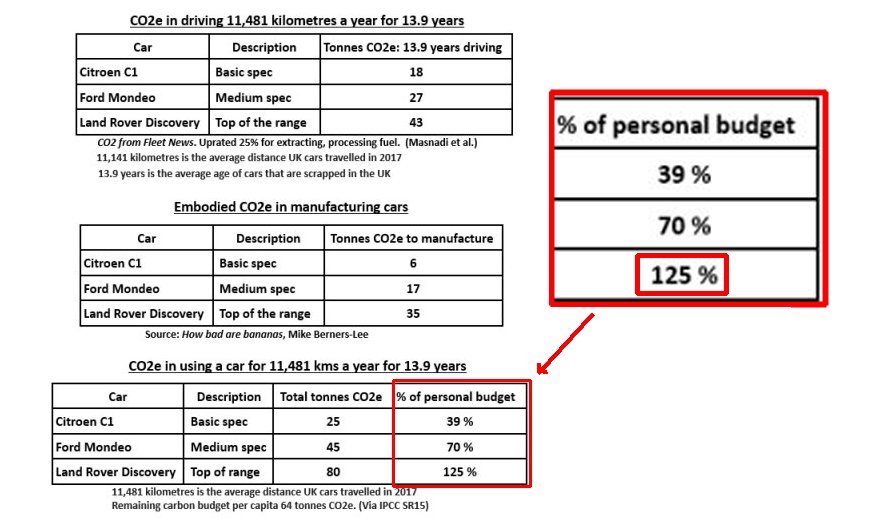

The IPCC special report, Global Warming of 1.5°C (SR15), gives a value for the global remaining carbon to give a 66% chance of the world’s surface temperature staying below a 1.5C rise above pre-industrial. This leads to a global remaining carbon budget of 64 tonnes CO2e per capita at the beginning of 2019. This personal budget can be swamped by one car in its lifetime.

According to a publication of the European Parliament in 2018 (Figure 5), the GHG emissions of mid-sized 24 kWh battery electric car is 10 tonnes CO2e for its manufacture. Over its lifetime (assumed to be 150,000 kilometers), the lifetime emissions amount to 20 tonnes CO2e using a typical mix of European electricity generation in a typical car’s lifetime of about 14 years.

Figure 5 shows the manufacturing emissions for internal combustion cars as 6 tonnes CO2e (with an additional 4 tonnes in the case of the mid-sized EV for battery manufacture). This seems significantly less than figures given by Mike Berners-Lee in How Bad are bananas for the manufacturing of cars. He gives the embodied CO2e in manufacturing cars as :

| Car Description | CO2e to manufacture |

| Citroen C1 | 6 |

| Ford Mondeo Medium spec | 17 |

| Land Rover Discovery Top of the range | 35 |

The difference between the two reports may be because the “24 kWh battery electric” of the European report was a Nissan Leaf, one of the lighter models of cars. (A search for “24 kWh battery electric car” returns the version of the Nissan Leaf with the smaller battery, with an official range of 124 miles).

Using Mike Berners-Lee’s figures gives the following:

This emphasises the conflict between keeping within carbon budgets and widespread personal vehicle ownership

[Note: consumption emissions]

The 2017 Global Carbon Project gives total global emissions as 41.2 GtCO2. Adding 30% to convert to CO2e gives 53.0 billion tonnes. That’s 6.9 tonnes CO2e per person in the world. In under ten years, this would exhaust the remaining carbon budget for keeping the Earth’s temperature below a 1.5C rise.

In 2016, UK emissions were 784 Mt CO2e. That’s 11.9 tonnes per person, exhausting the budget of 64 tonnes CO2e in less than six years.

[Note: UK leadership claims]

In their response to the CCC’s call for evidence the RTPI claim UK leadership in environmental planning:

The UK government should also seek to share and export the UK’s planning expertise, particularly concerning environmental planning, in which it is a world leader, to other markets and nations. This will disseminate and embed best practice globally, while also being as major commercial opportunity for UK PLC. Ourselves, the Royal Institute of British Architects, Royal Institute of Chartered Surveyors and the Chartered Institute of Building laid out how this can be done effectively in a joint letter.

The criticisms earlier doubt the reality of the RTPI’s grip on climate change but hopefully if any good expertise concerning environmental planning were developed in the UK, it could spread to the rest of the world.

The Secretary of State for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy, Greg Clark also makes claims to UK leadership on climate in response to the CCC’s ‘Net Zero’ report:

Few subjects unite people across generations and borders like climate change and I share the passion of those wanting to halt its catastrophic effects.

One of our proudest achievements as a country is our position as a world-leader in tackling this global challenge, being the first country to raise the issue on the international stage, introduce long-term legally-binding carbon reduction targets and cutting emissions further than all other G20 countries. Today’s report recognises the work we’ve done to lay the foundations to build a net zero economy, from generating record levels of low carbon electricity to our ambitious plans to transition to electric vehicles.

To continue the UK’s global leadership we asked the CCC to advise the government on how and when we could achieve net zero. This report now sets us on a path to become the first major economy to legislate to end our contribution to global warming entirely.

The policies of BEIS regarding climate change were criticised in the previous post, Carbon footprints and wildfires. If the UK is showing leadership, it is not leading in the right direction.

Postscript 15 September 2019: A design led approach

Amery Lovins of the Rocky Mountain Institute was a speaker at the 2019 Oxford Achieving Net Zero Conference. It was reported by Carbon Brief.

I made a comment after the piece, discussing the approach Amery Lovins makes to cutting energy use and carbon emissions. His is a design approach to creating new products and industrial processes which save energy and therefore carbon emissions.

I reproduce my comment, asking the question: If a design approach can be applied to products why can’t it be applied to settlements and lifestyles in a more radical way than is usual with current town planners so there is a recognisable market in life-styles. Then residents could choose the settlements they like? These, unlike most settlement choices now available on the market, should stay within planetary boundaries.

I have watched the Amery Lovins, Myles Allen and Rupert Read session – so far.

It raised …A QUESTION ON PATENTS

Amery Lovins put forward several ways of cutting carbon emissions through energy efficiency e.g. In moving liquids, smaller pumps with bigger pipes saved large amounts of energy. Another example was lighter carbon fibre cars, which use much less energy.

These energy savings result in much lower emissions and also lower costs achieved by better design.

Design is Amery Lovins’ key message: It is much more important than relying on breaking-news technology. He can show examples of where good design has made enormous increases in the energy efficiency.

In the discussion following, Rupert Read praised Lovins’ examples but said without a political framework, efficiency savings will produce further economic growth via rebound effects (i.e. the customers then have more money to spend on other things which lead to resource depletion and pollution.) Amery maintained any rebound effects had been shown to be small.

Rupert Read is right about the political framework but that Amery Lovins’ examples were excellent – saving loads of energy using better design rather than relying on cutting-edge technologies.

However, Duncan MacLeod from Lancaster University asked why Amery’ efficiencies had so often not materialised. For me, this raises the question of patents and IP. ‘Smaller pumps with bigger pipes’ may be a revelation but the idea is unlikely to be protected by patents. Are Amery’s designs held back for lack of patents?

However,remember that James Watt stifled other development with his patents and other patents stifled his development. The use of steam engines expanded greatly after Watt’s patents expired.(See Patents and Pollution)

Two questions:

1) How can we get good design used with no patents or other IP to drive it?2) Where ideas can be patented, how can the steam-engine-delay be avoided?

The video of the session can be found here.

TrackBack URL :